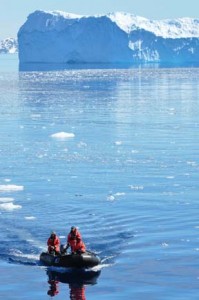

One hundred feet tall, two hundred beneath the sea, the massive “cubes” that are the remnants of a massive ice shelf-turned-berg called B15 bob along the Antarctic Sound. Once 160 miles long and 40 wide, the berg has diminished over 14 years courtesy of wind and water. Remaining still are these bobbing cubes and a single impressive stretch measuring more than 10 miles long. Soon it will be even smaller yet, pierced by blue crevasses and scarred by the ravages of cold and current. How this slice has even worked its way into this narrow stretch of Iceberg Alley is a mystery. Says the captain, “It’s like trying to wallpaper your apartment through a keyhole.”

Author Archives: Jane Wooldridge

Antarctic cycle of life

We wake to a bathtub ocean beneath a Brown Bluff, a volcanic ridge sheltering a sensitive Adele penguin colony. Hundreds of Adeles zip through the water, zipping in and out of the sea like porpoises, with the same splendid grace in water that they so sorely lack on land. At the water’s edge, battalions of black and white, march to and fro, neurotically debating whether to go into the sea – necessary if they want to eat – or whether to simply keep waddling nervously along.

Eventually, for most, hunger wins out, and they dip into the sea for a fish meal that they will ingest and then prepare as fuel for new-born chicks. Here there are many – some so new that they peck their way out of their shells as we watch. One parent closely guards the baby against a skua whose attempts to snag an egg or chick are foiled. If we have to leave, this is a splendid last stop on the White Continent.

Antarctica: Favorable winds

The winds have packed the ice in the Weddell Sea, making progress toward the emperor penguin colony impossible. We turn and sail instead into a gloomy afternoon. The weather turns, as it often does here, and soon we are again swimming in a vast and limpid sea beneath a clarion canopy. The orange light of the midnight sunset spills into a rosy glow. We sleep.

The winds have packed the ice in the Weddell Sea, making progress toward the emperor penguin colony impossible. We turn and sail instead into a gloomy afternoon. The weather turns, as it often does here, and soon we are again swimming in a vast and limpid sea beneath a clarion canopy. The orange light of the midnight sunset spills into a rosy glow. We sleep.

Antarctica, with comforts

Antarctica: An emperor (penguin) comes to visit

“Good morning Ladies and Gentlemen, good morning.”

During the night, we’ve entered the Weddell Sea. The usual morning greeting, from expedition leader Lisa Kelley, comes at 6:30 – earlier than planned. An emperor penguin has been spotted on the ice. It’s unusual this far north, but it’s early in the season, and in this atypically heavy season for ice, we’ve been afford this rare pleasure. “It’s not something you get on every sailing,” says naturalist Eric Guth. Camera shutters whir around us, snapping madly.

The emperor belly flops and toboggans a dozen feet to a group of Adele penguins. Intimidated, they immediately march off out of sight.

It’s a double treat. No sooner have we moved indoors and settled in with coffee then a second emperor is spotted. This one is far closer to the ship, and we’re able to grab photos of his (or her?) head, its eye patch rimmed in yellow. Like other penguins, the emperor colonizes for nesting, but before and after the season they often roam independently – solo travelers on a fish-eating mission. Because its gestation period last so long, emperors lay their eggs in mid-winter; by this part of the summer, their chicks can be left on their own while parents go off to feed.

A thousand images later, the ship sails deeper into the Weddell Sea. A pair of little Adele penguins flap their arms as we steam past their ice floe, as if signaling our path forward. The wind pops up, and they flop onto their bellies. The flurries begin.

Just as lunch approaches, and the jackets and gloves have gone back to their drawyers, Lisa’s mellifluous voice rings through the speakers. A leopard seal has been spotted up ahead. Time to grab the camera.

Taking the plunge, Antarctica style

The days are governed by skies, wind, ice and yet another splendid meal. A stunning clear morning is prime time for zodiac cruises around a glacier-rimmed bay,

past see-through arches carved in blue ice and confetti-like cubes strewn across the water. An unexpected apparition appears on the horizon: a Viking boat manned by two spike-helmeted Hagars. Patrik, the Swedish hotel manager, has arrived to serve us a surprise potion of hot chocolate, laced with a choice of schnapps or whiskey.

The fine weather continues; by afternoon, the temps have reached the 40s – too warm even for our fake-fur-lined parkas. Down-style jackets offer enough warmth for an hour of kayaking around the windless bay, trying to catch a photo of porpoising penguins and going close as we dare to the cerulean berg that oddly resembles the Grand Canyon. There’s time still for a visit to an old whaling station, long commandeered by wildlife. Gentoo penguins march along paths in the snow

from rookery to sea. The occasional skua lands in a rookery, trying to snag an egg. The penguins squawk madly and close ranks. A pod of Weddell seals snooze near the coast.

This fine afternoon, our expedition leader decides, is the perfect opportunity for the polar plunge. This is exactly what it sounds like – a leap into the frigid sea. The adventurous and foolish gather in the mud room – our usual staging place for Zodiac tours and shore visits – but this time without any clothing heavier than bathrobes. The appropriate attire for a plunge is a matter of individual choice; some are in shorts and Ts, others in bathing suits. The previous cruise, we learn, a guest has gone into the water in his tighty whities … a vision alarming enough to cause staff amazement weeks later.

The mud room has turned into a dance party of sorts. Patrik, the hotel manager, has revved up the tunes. The line to the kayaking platform from which we will plunge moves quickly, leaving little time for second thoughts. Down the steps, off the edge, into the sea – YOW! – and you’re quickly pulled out, then wrapped in a towel by the ship’s doctor, who stays close at hand.

Unlike the usual cold-weather swim when the water is warmer than air, in this case the water is at 30 degrees, with the air somewhat warmer. A shot of schnapps resets the circulation.

Antarctica: A clear day at the bottom of the world

Antarctica: Icy morn

Our morning goal is the Lemaire Channel, a dramatic narrow passage seven miles long and one mile wide. It’s a fine day, warm (by these standards, anyway) and windless, lenticular clouds spinning in the blue sky like alien ships. The ice crunches against our bow as our sturdy ship pushes through the pack ice, past penguins hanging out on the floes like some cartoon scene. “It’s beyond,” says Berryhil, a fellow traveler, using the word that somehow has become the trip’s theme. “Peaceful beyond peace,” says another ice watcher.

Our morning goal is the Lemaire Channel, a dramatic narrow passage seven miles long and one mile wide. It’s a fine day, warm (by these standards, anyway) and windless, lenticular clouds spinning in the blue sky like alien ships. The ice crunches against our bow as our sturdy ship pushes through the pack ice, past penguins hanging out on the floes like some cartoon scene. “It’s beyond,” says Berryhil, a fellow traveler, using the word that somehow has become the trip’s theme. “Peaceful beyond peace,” says another ice watcher.

Push as we might, the Lemaire Channel proves too clogged for navigation, and we slip back into the icy bay in search of whales and seals. A pair of humpbacks surface, rolling up but refusing to show us their flukes.

Antarctica: One fine day

The group before us has caught fine views of a humpback whale. By the time we clamber into our Zodiac and head out, the snow has started, and the whale has gone deep. We cruise the edges of the island, immersed in the elements.

The afternoon brings a steep, short climb to a gentoo penguin rookery. The snow is soft, causing potholing with nearly every step; to prevent penguin panic, we fill the whole back with enough snow to keep them from becoming stuck. A dozen or so birds march back and forth along a snow bank, anxious sentries uncertain whether to come or go. Up the incline, on the rocky nesting bed, one half of a feathery couple has burrowed down into the snow, building its nest beneath the surface. Its mate – heaven knows which is the male and which is the female – continually waddles to and fro, bring rocks and sticks to line the next. The deliveries go on and on for hours.

Post-dinner, we’re afforded a chance to go shopping at the small historic outpost of Port Lockroy. It is literally possible to use a credit card – anything except American Express – to purchase book marks and mugs and sweatshirts that help support the small museum dating from the 1940s, complete with the jarred marmite and canned tomatoes that serve as relics of an isolated life.

To visit, we need to park. Setting anchor is folly in seas hundreds of meters deep. Far easier, and more engaging, to bury the ship in an ice shelf and let us human penguins waddle about the ice. Usually the ice is too long melted, but because the ice has been late this year, we’re able to crunch out on the shelf in the fading (but never quite gone) light and romp right next to the ice-hardened hull. It’s a sight none of us could have imagined … made better with the assurance that unlike the Shackleton crew, we’ll be able to climb right back on board into the comfort of duvets and hot chocolate.

Antarctica: Our first landing, on Half Moon Island

The gusts are enough to throw an average sized person – or penguin – to the snow-packed ground. Your best hope is to put your back to the wind, bend your knees and tough it out.

The good news: the katabatic winds don’t last long, and we resume tromping along the packed “people paths” in search of photo opps.

We’re south now of 60 degrees – solidly in Antarctic waters and the forbidding, otherworldly surrounds that seem like some other planet. Greenland and Alaska seemed more hospitable than this jagged panorama of upthrust black stone crusted with ice; in those other rugged places, man has divined a way to co-exist with conditions. In Antarctica, only a handful of research stations operate year-round; anyone who has “overwintered” is a tough soul indeed.

As visitors aboard Lindblad Expeditions / National Geographic’s Explorer, we’re doing well just to untangle our camera gear – tomorrow we’ll carry less – pull ourselves from the occasional two-foot plunge through the snow pack (a stark reminder to stick to the “people path”) and troop around the rookery of chinstrap penguins. We’re following the rules and keeping at 15-foot distance between us and the birds, but the birds seem to have missing the memo and occasionally waddle over to check us out.

The black-and-white birds are as comical as a cartoon. Flippers flapping, they waddle until they belly-flop into the snow. Or better yet, the sea; its here that they fly, spinning through the ocean in watery flocks. It’s nesting season; no chicks for another week or so, but a bird still has to eat.

In this world, images don’t quite do the trick. But we’re giving this, literally a best shots, with the help of the expedition’s photo team. At each point of interest – near the Weddell seals at one end of the island, by the rookery on the ridge – a photographer answers questions and helps with camera settings while making sure none of the our fellow travelers gets too close to the birds.

We’re luck to have the landing at all, we learn. Our experienced team include a delightfully humorous German captain and an American expedition leader making her 121st voyage here. Thanks to their long experience and careful watch of ice and wind charts, they’ve steered us to sheltered bay where the winds allow us to go ashore. We learn this at the daily briefing, where the next day’s plans have been completely rewritten by high winds and a season of tough ice.